I had a brief impromptu twitter exchange yesterday with long-time publishing Insider Peter Ginna. The exchange emphasized to me the gulf which exists between those inside and outside the New York City lit-media bubble.

I mentioned to Ginna something I call the “Sholokhov-Solzhenitsyn Spectrum” of commitment to artistic integrity and freedom of speech. This, after he mentioned, in a positive way (he disputes this characterization), Simon & Schuster abandoning their commitment to publish free speech provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos after a flurry of protest by the established literary herd. I wondered where Mr. Ginna placed himself on that spectrum. Though he protested much that the “Big 5” combination of publishing conglomerates based in New York was “not a monolith,” he never answered my question.

****

Not surprising, in that Peter Ginna and myself come from different universes. On the subject of literature we speak different languages. At an age when he was attending Harvard and Oxford, I was working in the industrial bowels of Detroit—not the best training ground for a literary person, one would think. But my experiences gave me a sense of how this civilization works, as I saw in marine terminals and railyards how raw material is poured into a city, then creatively turned into something meaningful. It was also while clerking nights in a railyard at the heart of Detroit, near the fiery Rouge river, for many months, that to pass the time between trains I read, and read, and read—as comprehensive a syllabus as one could find at Harvard. If not Oxford.

While Ginna was paying his dues inside the bureaucracies of Big Publishing, I was paying my dues in the indy “zine” scene, creating not through staffs and levels of bureaucrats, but by hand, a series of publications, which I wrote, proofread, designed, drew on, colored, packaged—then marketed and sold. Every aspect of literary creation. On a vastly smaller level than the “Big 5” of course, with a more concise, more enthusiastic audience. It was a smaller scale view of literature, no doubt. The difference, perhaps, between the first Henry Ford making in a backyard shed an automobile out of bicycle parts—and his grandson “Hank the Deuce” inheriting a gigantic many-layered enterprise, in which someone at his level is far removed from the factory floor. Within which every aspect of the creative process—engineers; designers; marketers; accountants—is isolated from the others.

The result? With publishing, I sensed from my exchange a continuing sense of casual complacency, fluctuating from condescension in the face of contrary ideas, to upright defensiveness.

Yet if an automobile company can’t afford to be complacent (witness the events of 2008), how less can an art? And yes, literature is a business SECOND. First, it’s an art.

****

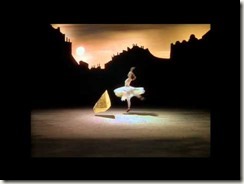

I thought of this last night, when my girlfriend (and NPL co-editor) and I watched the end of the classic 1948 film “The Red Shoes,” then followed this by viewing a 1967 Soviet movie version of “Anna Karenina.” Or at least tried to watch the latter, because every aspect of the Soviet film was awful. Particularly the casting and acting. The plot and much of the dialogue were taken from Tolstoy, but it wasn’t enough to save the flick.

We were forced to ask, “What happened?”

After all, in “The Red Shoes” the Russian impresario, dancers, artists, are all portrayed as geniuses. (Indeed, the movie itself is an unparallleled work of genius.) Yet the creators of the Soviet version of a classic Tolstoy novel were obvious dullards—going through the motions of creating a classic work of art but, like wooden puppets, lacking human or artistic spark.

We see two causes.

1.) The Russian characters in “The Red Shoes” would have to be expatriates who fled their native land after the Bolsheviks took power. Looking at the Soviet film, one can infer that the 1917 revolution and Bolshevik consolidation of power chased out—or liquidated—all creative talent. The premise no doubt was that new talent would rise up after the ostensible “liberation” of the masses—but it didn’t happen. Maybe because those masses were never really liberated, only further enslaved.

2.) One can see the difference between art produced by a tight group of creative talent, and that produced by a gigantic top-heavy bureaucracy required to conform to politically correct standards as laid down by political commisars. A ballet company, as shown in “The Red Shoes,” is a tight group of talented individuals each retaining their individuality. But so was “The Archers,” the film company founded by Michael Powell and Emric Pressburger, the geniuses behind the film. They not only had immense creative ability themselves, but, as important, the ability to spot and enlist other hyper-talented individuals into their project. Whether an actual Russian expatriate in the person of Leonide Massine, or the best cinematographer maybe ever in Jack Cardiff (the colors drip off the screen), or the surreally-talented actor Anton Walbrook and amazing dancer (and amazingly beautiful) Moira Shearer. The film is a paean to beauty, and to Art with a capital A.

The Soviet film? Merely a dud. The argument—my argument—is that massive bureaucracy, if too massive, in the realm of art if not autos, produces mediocrity.

Those involved in the creation of art should ask for more. Much more.